Pacific Northwest Magazine: Sunday, December 19, 2004

Home grown and highly prized:

From blankets to blazers, Pendleton creates a yearning for yarns

PHOTOS BY ALAN BERNER / THE SEATTLE TIMES

By Lynda V. Mapes

Pacific Northwest mazazine staff writer

PILED NEARLY head-high, these blankets, so thick, so soft, so brilliantly colored, ignite a rummaging instinct.

Hands rooting, heads down, conversation muted, shoppers — middle-aged white folks, New Agers, Indian people, snowy-haired retirees, the gamut — search the stacks with intensity.

On any given day, license plates on cars and tour buses from seven states can be seen in the parking lot of this store at Pendleton Woolen Mills in Pendleton, Ore. With customers from the longhouse to the clubhouse, few companies have earned such broad and deep loyalty. And one of the icons they seek is the Pendleton Indian trade blanket.

On any given day, license plates on cars and tour buses from seven states can be seen in the parking lot of this store at Pendleton Woolen Mills in Pendleton, Ore. With customers from the longhouse to the clubhouse, few companies have earned such broad and deep loyalty. And one of the icons they seek is the Pendleton Indian trade blanket.

Still made entirely in the Northwest, as it has been for 95 years, the blanket has cult status among collectors, especially Indian people, the company's first customers. When the early white traders came calling, their woolen blankets were among the few items that were actually high quality; their patterns were even created to appeal to Indian tastes.

Pendleton started its trade in Indian blankets in 1909 with the tribes of Eastern Oregon, and the blankets' popularity quickly spread. While other manufacturers of woolen trade blankets have come and gone in the Northwest, only one, Pendleton, remains.

And Native people buy more than half of the Indian blankets Pendleton sells. If it matters in Indian Country, it is celebrated with the gift of a blanket. And a Pendleton is the one everyone wants — despite its three-figure retail price.

But why blankets? And why Pendletons? These are questions that, among Indian people, always seem to astound.

"It is part of our cultural tradition," says Laverne Wyaco, a Navajo from Window Rock, Ariz., pulling a purple Pendleton from the stack. In town for a conference, "I had to come to the Pendleton store.

"We save up, pawn our jewelry, they are that important," Wyaco says. "When we have a ceremony, we have to wrap ourselves in a Pendleton, not a jacket. And it has to be a Pendleton. It's better quality."

The tradition is rooted just as deeply among Northwest tribes, where "a Pendleton" is synonymous with a blanket.

Each year when the Muckleshoot tribe holds a ceremony to celebrate the graduation of its kids from high school, every graduate is given a Pendleton. When the Skokomish people wanted to honor Indian elders for preserving Native languages, every elder was folded in the soft embrace of a Pendleton. And at a Tulalip ceremony in his honor, Democratic State Rep. John McCoy of Marysville, the first Washington tribal member in decades to serve in the Legislature, was wrapped in a chief's robe, a premium Pendleton bright as a longhouse fire.

Among Indian people, the importance of blankets dates back to when "a blanket could mean life or death," says Bruce Miller, a cultural and spiritual leader of the Skokomish tribe.

Robes from sea-otter pelts and buffalo skin, and blankets woven from mountain goat or dog hair were used before traders began arriving with wool blankets.

Warm even when wet, the woolen blankets were prized not only for their beauty but for cutting the damp, Northwest chill that leaked into uninsulated longhouses.

The blankets became a form of wealth, given in potlatch ceremonies, and used in trade and pawn.

In the nearly 100 years since, Pendleton has grown its product line to include everything from high-WASP navy blazers to custom camouflage, woven on contract, to Indian-blanket-patterned dog jackets and commuter bags.

The tribes? Some now operate casinos big as international airports. But the simple gift of an Indian trade blanket still has special meaning.

"When you cover someone with a blanket," Miller says, "you cover them symbolically with love."

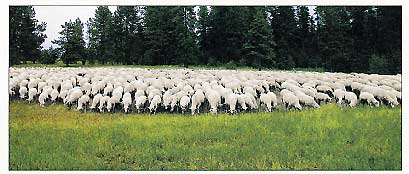

HIGH IN THE Blue Mountains above Pendleton, this band of more than 2,300 Rambouillet sheep is blissfully unaware of its venerable place in history.

But this January's clip, as the annual winter harvest of wool is known, will mark more than 70 years the Cunningham family farm has been raising wool for Pendleton Woolen Mills. Used in shirts and blankets, the creamy, vanilla-colored wool leaks like cumulus clouds from burlap bales, springy and pungent with the sheepy smell of lanolin.

Raising quality wool is no picnic, at least not for the grower. But for the sheep, that's exactly what it is: an endless summer ramble amid the sagebrush and Ponderosa of the Blues, stuffing themselves to their heart's content on belly-high grass.

Not a bad life, until, seven or eight years of grazing later, their teeth wear down. Hence the appellation "gummer," for a sheep whose number is up.

Sheep tender Wilfredo Palacios of Peru keeps watch over the band with help from his three crack herding dogs, Duque, Kevin and Pele. "You don't have dogs, stay home," Palacios says in Spanish.

Juan Erice, sheep foreman for Cunningham, brings Palacios a new box of food once a week and moves the camp trailer with a tug of his pickup to new grass. That's about it for entertainment for Palacios and his dogs, up there in the Blues with nothing but a bicycle, the tolling of the sheeps' bells and a big, wide sky.

Quiet and gentle with the dogs, moving slowly and patiently with the sheep, Palacios has what it takes to stay, alone, with a band of sheep, 24/7.

The Rambouillets make his work easier with the natural instinct of the breed to stick together. "You have one, you have them all," Erice says.

There is the occasional cougar to contend with, and maggot-laying flies that snug in wet wool after rain.

Dry years are actually worse. Then, sheep stick their heads into just about anything to find grass, forcing leaves, grasses, seeds, twigs and more into their fleece. The dreaded VM, or vegetable material, as it's known in the wool trade, lowers the yield and quality of the wool.

The goal is to produce a fleece so perfect it will please Dan Gutzman, a.k.a. Dan the Wool Man, manager of Pendleton's wool department. Gutzman searches out flocks on farms all over the world to find the right weight and type of wool for the right Pendleton product, be it shirt, blazer or blanket.

He is a second generation "brother of the fleece." Members of this tiny cadre of experts are professional wool buyers, fiber fanatics, able to tell the tensile strength of wool right off the sheep with a tug, and the diameter of its fiber within half a micron at a glance.

About half the wool Pendleton uses comes from the U.S. The wool from five countries might be in a single blanket.

Gutzman plunges his hand up to the wrist into a fleece in the back of his truck, pulling out fibers to demonstrate their length, crimp, strength and size, all crucial to the "confession," or price a wool buyer will offer for fleeces at auction.

It's cushy work, literally: "Baby-butt hands," Gutzman says, holding out pink, tender palms, the result of years of lanolin-soaked labor.

"My wife likes it."

IN THIS FACTORY, even the repair-shop pin-up girls wear not the usual brief bikinis — or less — but Pendleton blazers and skirts with a demurely jazzy flair.

The forklift sports a Pendleton cover. And bits of wool, soft as chick fluff, kite around in the air as machines spin yarn by the mile.

The only remaining woolen mill in Oregon, the Pendleton plant is a mix of new and old. Patterns on computer disks are loaded into state-of-the-art machines that can weave a blanket in more than a dozen colors in 24 minutes. In another wing of the building, cast-iron carding and spinning machinery still sports leather drive belts.

The company's history shows at Pendleton's Washougal plant, too. The newest wool-processing equipment, installed in a $50 million upgrade, keeps company with floors velvety from years of lanolin tread into the wood. A high-water mark shows where the Columbia used to flood the building before the river was dammed.

Both the Washougal and Pendleton operation are union plants, with average wages of about $12.50 an hour, and a workforce in which careers spanning more than 20 years are not unusual.

Threads hanging from her hair, there is no doubt that Carole Carnes, a 21-year veteran of the Pendleton plant, is deep in her job, mouth pursed in concentration as she checks rolls of woven blanket fabric for extra threads or flaws. She plucks out errant threads with a pair of tweezers held on her wrist with a leather thong. "I always have lint in my hair when I go home," she says.

At this stage, the fabric looks more like a towel than a blanket. Finishing machines at the Washougal plant create the blankets' characteristic soft, napped feel.

Each blanket will be inspected again at Washougal, where workers examine every one by hand.

Finishers cut the blankets to length, label them, sew on the felt binding and box them. Hand-folding the blankets just so, for neat presentation in that classic blue-and-yellow-labeled Pendleton box, is the slowest step in the process.

Organized into teams of eight, the blanket finishers each have their own team name and charter, such as these "Words to Work By," posted at The Wildflowers' work station:

"We come to work on time

Like a ray of sunshine

Quality is a major goal,

Satisfaction for our soul."

SIR WOOLIAM, the Pendleton mascot, is grazing new pastures.

The stuffed sheep — life-sized — holds court at the company's Portland home store, amid a line of home furnishings intended to appeal to a new kind of customer.

Indian trade blankets still form the store's "power wall," as Bob Christnacht, manager of Pendleton's blanket and home division, calls it. "That brings them in the store."

But once they get there, customers will see not only vibrant Indian trade blankets but a summer-weight Pendleton blanket in solid, soft, butter yellow, and fern-patterned curtains, duvet covers and luxury linens. Home products with no hint of a Western, or Indian, theme at all.

"The nongeometric designs, that's a departure for us," Christnacht says. "We are really working both sides of the market, the Pacific Northwest and the European luxury-style customer."

The company is also opening more of its own retail stores — including one at Alderwood earlier this fall — to better promote its brand, rather than depend on department stores to do it for them.

C.M. "Mort" Bishop III, the fifth-generation president of Pendleton, said the new products and retail push are part of the company's decision to grow its brand beyond the Indian blanket and nostalgic niche as the company everyone's grandfather bought their best wool shirt from.

"We love the warm memories of Pendleton. The challenge is to see that we have relevance in current lives. What we love to hear is, 'This is Pendleton? I didn't know you made this.' "

The company also began over the past 10 years to source some products, including cotton shirts, silk sweaters and leather jackets, from out of the country. And it now finishes some of its trademark items, including wool shirts, outside the U.S. Sending pieces of the shirts to Mexico for sewing means the company can sell the shirts for $20 less each, Bishop says.

"It was the only decision we could make, and a huge change. We would not have entered a new century if we stayed true to our made-in-America roots."

Pendleton cut about 800 jobs and shuttered plants across the country, a painful move for a company Bishop described as "paternalistic," where some workers' families had been with the company for generations.

"The big difference in a family business is the long pull, making decisions for the future, not just anonymous stockholders. It has been a difficult transition, these last 10 years, going from a totally made-in-America product line to a balance of international and domestic sourcing.

"We are not keeping everything here, and we are not sending everything overseas. It's not extreme, it's measured. It's about balance, and it's very healthy for us."

Walking past a table spread with new designs and products in the works for the coming year, Bishop points to garments he says the company never could have made if it didn't turn outside this country for suppliers and manufacturing.

Even the Indian blankets, while still made here, are changing. The line will soon include a new Urban Tribe Collection for spring 2005, with designs intended to depict the totems of new types of "tribes" — groups of people sharing a common interest: Urbanites, coffee drinkers, commuters tied up in traffic, wine connoisseurs, maybe even soccer moms. "Everyone belongs to some kind of tribe," Christnacht says.

To Bishop, the company's future is about holding on to the right amount of its past.

"We have to write new chapters, we can't stagnate and live in our own world. But it's very important for us to maintain our history and our heritage.

"Some companies have become just a shell. But there is still a place called Pendleton in a Pendleton."

Lynda V. Mapes is a Seattle Times staff writer.